2009 is the 8th year for the George Walker House to be host site for The Hummingbird Monitoring Network. Seems the Broadtails always come in after banding. As does a good afternoon nap!

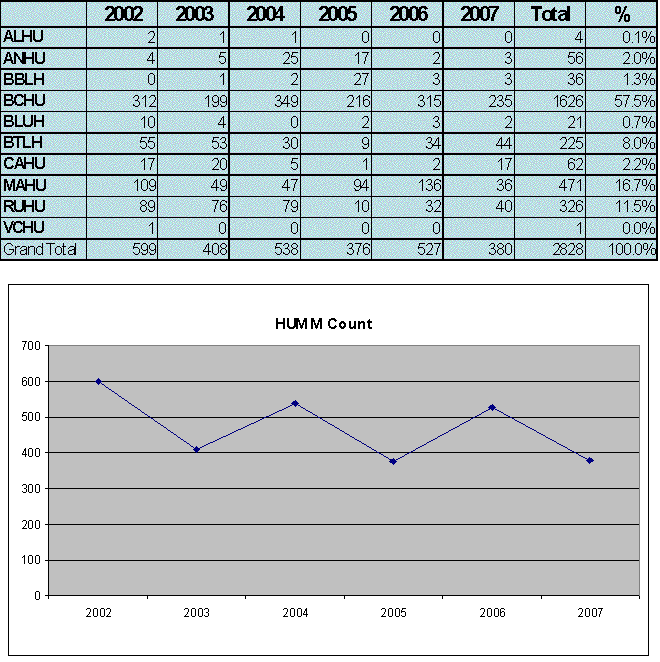

2002 - 2007 Summary

2005 Paradise Banding Site Summary

Apr

|

May

|

Jun

|

Jul

|

Aug

|

Sep

|

Oct

|

Total

|

|||||||||

2

|

3

|

17

|

1

|

15

|

29

|

12

|

26

|

10

|

24

|

7

|

21

|

4

|

18

|

2

|

||

Anna's

|

1

|

1

|

15

|

17

|

||||||||||||

Black-chinned

|

21

|

19

|

18

|

14

|

63

|

5

|

1

|

5

|

6

|

15

|

32

|

14

|

3

|

216

|

||

Blue-throated

|

1

|

1

|

2

|

|||||||||||||

Broad-tailed

|

1

|

2

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

9

|

|||||||

Calliope

|

1

|

1

|

||||||||||||||

Magnificent

|

2

|

1

|

4

|

6

|

5

|

25

|

21

|

1

|

3

|

22

|

4

|

94

|

||||

Rufous

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

2

|

2

|

10

|

|||||||

Grand Total

|

3

|

1

|

28

|

25

|

24

|

40

|

86

|

5

|

2

|

10

|

7

|

17

|

38

|

39

|

24

|

349

|

2004 Paradise Banding Site Summary

Date

|

18-Apr

|

2-May

|

16-May

|

30-May

|

12-Jun

|

27-Jun

|

11-Jul

|

25-Jul

|

8-Aug

|

22-Aug

|

5-Sep

|

19-Sep

|

4-Oct

|

18-Oct

|

TOTAL

|

Species

|

|||||||||||||||

Black-chinned

|

19

|

20

|

8

|

20

|

69

|

*

|

8

|

1

|

23

|

129

|

48

|

1

|

346

|

||

Rufous

|

2

|

1

|

1

|

7

|

17

|

46

|

6

|

80

|

|||||||

Broad-tailed

|

*

|

4

|

1

|

3

|

2

|

16

|

4

|

30

|

|||||||

Magnificent

|

2

|

5

|

1

|

7

|

20

|

*

|

*

|

2

|

3

|

7

|

47

|

||||

Calliope

|

2

|

3

|

5

|

||||||||||||

Blue-throated

|

|||||||||||||||

Anna's

|

1

|

1

|

2

|

5

|

12

|

5

|

26

|

||||||||

Allen's

|

1

|

1

|

|||||||||||||

Broad-billed

|

1

|

1

|

2

|

||||||||||||

Total

|

23

|

26

|

9

|

27

|

94

|

0

|

1

|

11

|

5

|

32

|

157

|

129

|

23

|

537

|

2003 Paradise Banding Site Summary

Date

|

23-Mar

|

6-Apr

|

20-Apr

|

4-May

|

18-May

|

1-Jun

|

15-Jun

|

29-Jun

|

13-Jul

|

27-Jul

|

10-Aug

|

24-Aug

|

7-Sep

|

21-Sep

|

5-Oct

|

TOTAL

|

Species

|

||||||||||||||||

Black-chinned

|

0

|

11

|

27

|

22

|

12

|

26

|

25

|

0

|

4

|

14

|

13

|

16

|

26

|

4

|

200

|

|

Rufous

|

0

|

4

|

1

|

1

|

3

|

11

|

23

|

12

|

12

|

8

|

75

|

|||||

Broad-tailed

|

0

|

8

|

5

|

3

|

3

|

4

|

0

|

0

|

3

|

6

|

8

|

14

|

1

|

55

|

||

Magnificent

|

0

|

5

|

3

|

9

|

1

|

8

|

10

|

0

|

0

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

1

|

49

|

||

Calliope

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

3

|

8

|

3

|

4

|

20

|

||||||||

Blue-throated

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

|||||||||||||

Anna's

|

1

|

1

|

3

|

5

|

||||||||||||

Allen's

|

1

|

1

|

||||||||||||||

Broad-billed

|

1

|

1

|

2

|

|||||||||||||

day

|

0

|

29

|

36

|

35

|

16

|

34

|

39

|

0

|

4

|

19

|

34

|

59

|

57

|

35

|

13

|

410

|

2002 Paradise Banding Site Summary

May

|

Jun

|

Jul

|

Aug

|

Sep

|

Oct

|

Total

|

|||||||

5

|

19

|

3

|

16

|

30

|

14

|

28

|

11

|

25

|

8

|

22

|

6

|

||

Allen's

|

2

|

2

|

|||||||||||

Anna's

|

1

|

1

|

2

|

4

|

|||||||||

Black-chinned

|

36

|

36

|

57

|

35

|

2

|

4

|

25

|

15

|

38

|

44

|

19

|

1

|

312

|

Blue-throated

|

1

|

5

|

2

|

2

|

10

|

||||||||

Broad-tailed

|

8

|

4

|

6

|

7

|

9

|

10

|

5

|

2

|

4

|

55

|

|||

Calliope

|

6

|

4

|

2

|

5

|

17

|

||||||||

Magnificent

|

5

|

9

|

37

|

12

|

1

|

1

|

11

|

12

|

13

|

7

|

1

|

109

|

|

Rufous

|

1

|

13

|

23

|

20

|

16

|

14

|

2

|

89

|

|||||

Violet-crowned

|

1

|

1

|

|||||||||||

Grand Total

|

50

|

49

|

106

|

54

|

3

|

7

|

55

|

65

|

80

|

82

|

45

|

4

|

600

|

The following is extracted from their promotional leaflet:

In 2002, we began a hummingbird research project with the following goals: to determine the best long-term monitoring sites for hummingbirds in western USA and northwestern Mexico, to learn how to effectively sample their population sizes, and to use the resulting information to assist in their preservation and protection. In North America, hummingbird diversity is highest in southwestern USA and most of these species are dependent on habitats in Mexico for their winter survival and, for some, breeding.

This research generates knowledge about hummingbird diversity, abundance, productivity, and survivorship in a variety of habitats. Study sites occur in vegetation zones at different elevations, longitudes, and latitudes. It is a systematic banding study that will detect movement patterns for many hummingbird species in western USA and eventually northwestern Mexico. It defines a methodology that when used by others will yield data that can be statistically compared. Thus, we can begin to understand how hummingbird diversity varies from place to place and from region to region and how hummingbirds move through these regions. The results of the research should provide land managers with information about which areas support a high diversity of hummingbirds, the timing of their occurrence, and seasonal movement patterns that may indicate the size of the areas needed to maintain hummingbird diversity and abundance. It also has provided and will continue to provide training for students, scientists, and members of the general public in the skills required for hummingbird study. Because hummingbirds capture people's imagination, they are excellent subjects for conservation education, one of our main objectives.

For this project, we band hummingbirds once every other week from mid-March to late October. Banding techniques allow researchers to assess population sizes of hummingbirds and other landbirds. Our banding occurs at multiple sites at different elevations, longitudes, and latitudes in a variety of vegetation zones. Each banding session lasts five hours and begins within one half hour of sunrise. Because banding at each site follows a standardized methodology, changes in species occurrence and abundance patterns can be compared among years and among sites. Analyses of these data will help identify important areas for hummingbird migration and breeding. At the end of a season, results from each site are evaluated to determine which sites are still contenders for long-term monitoring sites or if a new site should be added and evaluated. Because hummingbirds have unique flight abilities and require specialized permits to work with them, other avian conservation programs such as MAPS (Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship) fail to adequately sample hummingbird populations.

In 2003, we have expanded to 14 study sites in Arizona and 5 in California. This project is an extension of the Migratory Pollinators Program of the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum (ASDM) and has involved many partners of DSCESU. Two of the primary investigators are associated with partners of DSCESU: Ms. Carlson is the Director of 3 Natural Reserves for the University of California at Riverside and Dr. Wethington is a research associate at the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum. We are also working in three National Parks: Tumacacori National Historical Park, Coronado National Memorial, and Chiricahua National Monument, on BLM land in California, and will soon start a site on US Forest Service land. Additionally, we work with many private landowners as well as a prospective new DSCESU member.

If you are interested in becoming a citizen scientist and joining this all volunteer project, please let the banding team know and they will give you a card with contact information.

The following proposal describes the banding study.

A Proposal for a Multi-Member Cooperative Project of the Desert Southwest Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit

By

Susan M. Wethington Ph.D., Barbara A. Carlson, and George C. West Ph.D.

Hummingbirds are great “Marquee Species”. They are a highly visible, attractive, and well-known family of birds that fascinate all who see them. In Canada and the U.S.A, their diversity is greatest in the Desert Southwest Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit (DSCESU) region where they occur in virtually all habitats. Different species depend on specific habitats such as riparian zones, forests, and arid desert regions. Thus, when land managers and conservation professionals protect and preserve habitat for hummingbirds, they also protect habitat for a suite of less visible but more threatened and endangered species.

The Hummingbird Monitoring Network (HMN) is a group of scientists, citizens, land managers, and property owners who are committed to the conservation of hummingbird diversity and abundance. Our work provides land managers with information about which areas support a high diversity and abundance of hummingbirds, which areas are important breeding sites, the timing of their occurrence, and seasonal movement patterns that will help define the areas needed to maintain this diversity. Ultimately, our goal is to develop an effective hummingbird conservation program that will include monitoring, research, education, and preservation projects.

Currently, HMN works with many DSCESU partners in Arizona and California. Our work remains consistent with the basic vision of a CESU, which is to facilitate collaborative research and to provide education and technical assistance opportunities that address ecosystem resource issues at local, regional, national, and international levels. HMN is growing rapidly. By the end of the year, we will be working not only at one of the northern centers of hummingbird diversity, which is the DSCESU region, but also near the center of their diversity, which is near the equator in South America.

Our monitoring work also is generating research questions that address ecosystem resource issues. These questions include “How does off-highway vehicle use of a riparian habitat affect hummingbird productivity?” and “What fire regimes or histories benefit populations of plants that provide nectar for hummingbirds?” These questions require expertise, which current members of the DSCESU have. Help in building partnerships to address these questions will ensure that the best expertise is used to answer them. In return, the large number of hours, donated by volunteers in the monitoring program, provides substantial matching grant funds. With these matching funds, we can then seek funding for these new collaborative projects from additional sources.

This proposal requests support of DSCESU members for our monitoring work, for partial salary of its director, and for help in building partnerships to answer research questions. Support of monitoring is organized on a site basis. Depending on the number of censuses and on travel costs to be negotiated with each site host, the cost varies between $4,000 to $8,000 per site per year. Agreement to fund a particular site(s) should be for a minimum of three years. With three years of data, we can evaluate the site's monitoring importance. However, results from each site are evaluated at the end of each season and for sites that prove not to be important monitoring sites, we often know after a year or two.

SUMMARY

In 2002, we began the HMN with the following goals. 1) To determine the best long-term monitoring sites for hummingbirds in western USA and northwestern Mexico; 2) to effectively sample their populations sizes so that trends can be detected; and 3) to use the resulting information to assist in their preservation and protection. Our research is a systematic study that generates knowledge about hummingbird diversity, abundance, productivity, and survivorship in a variety of habitats. Initially, we choose study sites in these habitats based upon geographic factors (elevation, longitude, and latitude) and vegetation types. At these sites, we trap and band hummingbirds once every other week from mid-March to late October and use other counting techniques to assess their population sizes. Because banding at each site follows a standardized methodology, changes in species occurrence and abundance patterns can be compared among years and among sites. Thus, we are beginning to understand how hummingbird diversity varies from place to place and from region to region and how hummingbirds move through these regions.

HMN started with 9 study sites in Arizona and 2 in California. In 2003, we expanded to 14 sites in Arizona and 5 in California and will expand to New Mexico, Texas and northwestern Mexico as resources permit. Now, we work in three National Parks (Tumacacori National Historical Park, Coronado National Memorial, and Chiricahua National Monument), on US Forest Service land, and in two Nature Conservancy preserves in Arizona. In California, we work on BLM land, UC Riverside Reserves, and National Audubon Preserves. In both states, we work with many private landowners. Additionally two of the primary investigators are affiliated with DSCESU partners. Dr. Wethington is a research associate at the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum. Ms. Carlson is the Reserve Director for the University of California at Riverside.

Last fall, we submitted a proposal to a number of DSCESU members. It contains more information about our monitoring project and our site evaluations for 2002. It is available on request.

CURRENT STATUS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

At last spring's Executive Committee meeting of the DSCESU, we introduced our monitoring program, presented the results of the 2002 field season, and described our vision of expanding the project into a full conservation program for hummingbirds. In this section, we wish to provide an update on our work in 2003. The monitoring network has and is growing with new involvement by students, researchers, and the public and with the definition of new research projects. Much of this growth would not have been possible without the financial support given by the NPS DSCESU partner and IMRICO.

Monitoring

Monitoring Goal 1: Determining the best long-term monitoring sites.

In 2003, we expanded to 14 study sites in Arizona and 5 in California. Our field season lasts through October. So, this year's evaluation of the sites and coverage for all hummingbird species has not been completed. Many of our sites are contenders for long-term monitoring, of which one is TNC's Aravaipa Preserve. This preserve is likely at the northern breeding range of two species, Broad-billed and Violet-crowned Hummingbirds and is a breeding site for Black-chinned Hummingbirds.

Because this area is an important breeding site, we have begun to evaluate our productivity measure. We can detect breeding only when a female is developing an egg. Once the egg is laid, we are unable to detect an incubating female because hummingbirds do not develop a brood patch like other landbirds. Thus, we are able to detect breeding in females for only four days out of a breeding cycle, which is approximately six to seven weeks long. It is also likely that some species, such as the Broad-billed Hummingbird, are less likely to be captured while gravid. Hence, our productivity measure needs to include field data with nest counts and fledgling success rates.

With this need to improve our productivity measure, we began to investigate study areas around Aravaipa Canyon and have identified BLM's Turkey Creek, a tributary to Aravaipa Creek, as a likely candidate. Here, we observed Broad-billed Hummingbirds maintaining territories and saw young later in the season. As we talked with TNC's preserve manager, Mark Haberstich, we realized that our work to define a better productivity measure could also provide information that may help TNC and the BLM manage this area. Mark has expressed concerns that the increased use of Turkey Creek by off-highway vehicles is having adverse effects on the health of this riparian zone. Hence, we would now like to ask the research question: “How does off-highway vehicle use of a low elevation riparian zone affect hummingbird productivity?” Please refer to the Research section for more information.

Monitoring Goal 2: Estimating population sizes so that trends can be detected.

In 2002 and 2003, we have six Arizona sites in common. Using our data for the breeding season, May through July, we have found a significant decline in the number of hummingbirds. The average number (±SD) of hummingbirds per banding day was 64±58 in 2002 and 27±19 in 2003 (paired t test, P < 0.001, t = -4.08). At one of our sites, banding has occurred for four years. There, the number of hatch year hummingbirds, those successfully fledged in a year, has declined from 27.5% in 2000 and 23.6% in 2001 to 14.9% in 2002 and 16.6% this year. This trend suggests that the severe drought of recent years have seriously decreased hummingbird populations. However, two years of data at multiple sites and four years at one site are not sufficient to suggest a trend. We also do not know if it actually represents a decline in the population. One of the challenges in estimating hummingbird populations is to determine how the number of flowers in an area affects the visitation rate at feeders. Based upon one Colorado study, the expected pattern is for the visitation rate at feeders to decline when more flowers are available.

Currently, a study that asks this question, how does flower density affect hummingbird visitation rates at feeders, is underway at Tohono Chul Park. Here, there are a number of gardens planted with hummingbird visited flowers and the flower density varies throughout the year. We are working with Martha Pille, a retired microbiologist and a docent at Tohono Chul, and with a doctoral graduate student, Rachel McCaffrey, from UA's Renewable Natural Resources (RNR) department. Martha has mapped the gardens so that we now know the size of these flower patches and has proposed a measure for defining flower density. Rachel will now be responsible for completing the experimental design and carrying out the study with the help of the Tohono Chul Docents.

Although the above study begins to give us a way to adjust our hummingbird population estimates, we still need to determine how to estimate flower density and its effect on feeder visitation at the landscape level. This needed research will be integrated into our research question about fire history affects on populations of plants that provide nectar to hummingbirds. Please refer to the Research section for more information.

Monitoring Goal 3: Using the information to assist in the preservation and protection of Hummingbirds.

We are completing our second year. Thus, we have limited information on which to suggest conservation actions for hummingbirds. However, our work in Aravaipa Canyon has suggested additional research studies about hummingbird productivity and land-use policies. This research could yield important information for land management decisions.

In addition to our scientific data, the large number of hours donated by the citizen scientists and volunteers translates into substantial matching grant fund for beginning our preservation section. Consequently, we are now actively developing a preservation project in Ecuador. Please refer to the Preservation section for more information.

Education and Outreach

Community Goal 1: Training and working with citizen science teams

The success of our project depends on the commitment of citizen science teams and dedicated volunteers. Consequently, we have provided and will continue to provide training for students, scientists, and members of the public in skills required for hummingbird study.

People who train to be banders and to manage a monitoring site are considered citizen scientists. They are responsible for all work at a site. This includes strict adherence to the project's protocol, banding hummingbirds, ensuring that the data are taken correctly and accurately, submitting reports and the banding data after each session, working with the site hosts, and managing the other volunteers needed to successfully complete a banding session. With these expectations, we have found that people are truly committed to the project. In Arizona, we have five teams of dedicated citizen scientists. The California team will expand next year. Ms. Carlson has been training banders and expects to fledge three, possibly four citizen scientist teams for 2004.

We are impressed by the commitment of these citizen scientists. Two from the Arizona team, Rebecca Hamilton and Susan Campbell, went the extra mile. They made the additional commitment to become certified as hummingbird banders by the North American Banding Council. This certification indicates that they are qualified to run a hummingbird banding station anywhere in the USA and if they wished, to obtain a master banding permit from the USGS Bird Banding Laboratory.

Community Goal 2: Partnering with land managers

Working with land managers, both public and private is essential to the success of this project. As mentioned earlier, we have successful partnerships with many DSCESU members and with many private landowners. Please refer to the Building Partnerships within the DSCESU section for more information.

Community Goal 3: Increasing public awareness and understanding of hummingbirds

In 2003, many of our sites, including TNC's Ramsey Canyon Preserve and BLM's Big Morongo Preserve, are open to the public. At these sites, we inform the visitors about the project, the importance and inter-relatedness of hummingbirds in the natural world and teach them about hummingbird biology. Often, visitors leave with a sense of wonder for hummingbirds.

Additionally, NPS and IMRICO have funded a brochure and website for HMN. These educational tools are currently being developed. The brochure will be completed by the end of 2003 and will greatly enhance our ability to reach visitors at our public sites. The website, which should be online by spring 2004, will describe our project, present many of our results, educate the public about hummingbird diversity, and inform how interested individuals can become involved. In today's electronic age, a website is essential for public outreach and education.

Preservation

Our preservation program began on May 3, 2003 at the Cooper Ornithological Society's annual meeting. Dr. Becker presented information about the high number of endemic and endangered species supported by the Loma Alta Ecological Reserve in Ecuador. This reserve, owned and protected by indigenous people, supports 42 of the 55 endemic bird species of the region. It is also a hummingbird oasis in that important nectar resources grow in the cloud forest of the reserve. Twenty-eight hummingbird species occur there, including the critically endangered Esmeraldas Woodstar. Dr Becker's research and others on the conservation value of the birds of Loma Alta recently resulted in its classification as an International Important Bird Area.

Later, Dr Wethington introduced HMN, presented the results of the first year of hummingbird monitoring, and expressed an interest in beginning a full conservation program using the volunteer hours as collateral. Drs Becker and Wethington have joined forces in helping to continue the preservation of Loma Alta's watershed. First, we wish to build an interpretive center at El Suspiro village in Loma Alta that explains the importance of preserving native habitats from the ocean to peaks of the region and their links with the Andes. Currently, most members of the community live in poverty. Thus, we would also like to find ways in which the members can make a sustainable living without impacting their resolve to protect the forest. We are actively pursuing opportunities for funding these projects.

Our collaboration continues to grow with combined research this winter in Loma Alta. Dr. Wethington will assist Dr. Becker on her Earthwatch Cloud Forest Bird research. In addition to her landbird censuses, we will compare hummingbird diversity and abundance along an elevational gradient using the methodology defined by HMN. We will also compare two capture techniques: the trapping done by HMN and the mist nets used by Dr. Becker. One of Dr. Becker's challenges has been obtaining data on the endangered Esmeraldas Woodstar, a hummingbird that weighs only 1.5 grams and escapes capture in the mist nets. This research has incredible potential for increasing our understanding of hummingbird diversity and how it varies between the tropic and temperate regions of the Western Hemisphere. Hummingbirds occur in the New World only, are most diverse in the tropics with over 130 species in Ecuador alone. They show a strong latitudinal gradient with the American southwest being the furthest northern center of their diversity, where only 16 species regularly occur.

Additionally, this winter's work may be featured in a documentary about Loma Alta and hummingbirds. This opportunity has just presented itself to us and we are actively considering it.

Research

This section of the program is in its infancy. We will continue to refine the following research questions through fall and spring. At which time, we will be looking for funding. We welcome any help that DSCESU members wish to offer and are particularly interested in building new partnerships for questions 1 and 3.

Research Question 1: How does Off Highway Vehicle (OHV) use of a low elevation riparian zone affect hummingbird productivity?

Background: HMN needs to refine its productivity measure so that it better reflects hummingbird productivity of an area. Thus, we need to add field data such as nest counts and fledgling success rates to our protocol. While refining our productivity measure, we have the opportunity to define an experiment that could affect land management policy in a riparian zone. Please refer to the Monitoring section under goal 1 for more information.

Importance: The importance of riparian zones for the survival of many wildlife species is well documented, as is the loss of riparian zones in the arid southwest. If we find support that OHV use of BLM's Turkey Creek lowers hummingbird productivity; it is likely that the effect on hummingbirds would provide enough justification to change the land use policy of this riparian zone.

Approach: With the help of land managers and/or scientists from BLM and TNC, we will identify study areas that can be compared to Turkey Creek. We will conduct nest searches and quantify nesting success in Turkey Creek, with and without OHV traffic, and in each of the other comparable areas. Nesting success will then be compared to determine the effect of OHV traffic on hummingbird productivity.

Research Question 2: How does flower density affect visitation rates by hummingbirds to feeders?

As mentioned earlier, Rachel McCaffrey, a doctoral student in RNR at UA, now leads this research. She is currently working on the experimental design. It will occur on the grounds of Tohono Chul Park and Tohono Chul docents will provide field assistance. We expect fieldwork to begin sometime this fall or winter. The results of this study will help us determine how to estimate hummingbird population sizes more accurately.

Research Question 3: What fire histories and/or management practices benefit populations of plants that provide nectar for hummingbirds?

Background: Critical resources for maintaining hummingbird diversity and populations are the nectar resources on which they rely. Many of these plant species occur in early successional stages of a forest and it is expected that the fire history of a forest will affect the overall abundance of these nectar resources. In addition to determining how fire management might benefit this important resource for hummingbirds, we also need to develop a relative abundance measure of these resources. It will be used in association with our monitoring data to help estimate hummingbird population sizes. The current collaborators on this project are Dr. Anthony Povilitis, founder of the Cochise Conservation Center, and Dr. Wethington.

Importance: Wildfire is a hot topic in the American West, and different, often conflicting, strategies for controlling or managing it have been proposed. Information is needed to determine how different fire regimes affect the region's biological diversity. We wish to investigate how fire affects foraging habitat for hummingbirds, an important component of biodiversity in the Southwest.

Approach: Multiple approaches are currently being discussed. One approach examines the relationship between hummingbirds and post-fire communities focusing on host plant distribution and abundance, and considering factors such as time since burn, habitat type (elevation, vegetation, aspect, slope, etc.), precipitation, burn size and pattern, and intensity of burn. Steps in this approach include 1) selection of burn sites and controls, 2) spring-summer inventory of host plants involving a) general observations and possible photographic documentation, b) vegetation plots for obtaining quantitative (density of plants, or flowering stems) and qualitative data (some measure of plant vigor), and 3) supplementary observations/data collection on hummingbird species, their abundance, and host plant use.

Research Question 4: Are hummingbird diversity patterns along an elevational gradient similar in the tropics and temperate regions?

Please refer to the Preservation section for more information.

BUILDING PARTNERSHIPS WITHIN THE DSCESU

HMN sees many opportunities for building partnerships within the DSCESU. Our monitoring work involves many of you. In most cases, we have volunteered our time and skills to build these partnerships. Financial support at the site level is essential for our continuance. We believe that we have reached the limit on what is viable and appropriate to ask of volunteers. However, we expect the project to always have a strong volunteer component. Hummingbirds capture people's imagination and these citizens want to help.

Our monitoring work fuels the remaining sections of HMN's conservation program. Its results directly influence the definitions of the research questions, described above. Investigating these questions will provide new opportunities to involve the technical expertise of your member institutions. Results of these investigations will likely have important implications for land management decisions. For information about current and some potential partnerships with HMN, please refer to Table 1.

CONCLUSIONS

The Hummingbird Monitoring Network embodies the vision of a CESU. It is a project of regional and soon to be international scope. It has the potential to involve all members of the DSCESU. Land Managers, who support the monitoring effort, help discover hummingbird diversity patterns needed to protect them and to raise conservation awareness among the public. Universities, non-profit organizations, and government agencies have expertise critical for answering research questions that could have direct impact on land-management decisions. HMN provides many opportunities for individuals in the United States and, one day, in Mexico to become involved with citizen science. It has provided and will continue to provide training for students, scientists, and members of the public in the skills required for hummingbird study.

The wonder of hummingbirds can be a powerful conservation tool. While preserving hummingbird diversity, the potential to preserve other more threatened and endangered species is real. Our motivation is simple; we cannot imagine a world without hummingbirds and we do not know enough about their diversity patterns, population ecology, and movement patterns to make effective conservation decisions to protect them. Because they have unique flight abilities and require specialized permits to work with them, other avian conservation programs such as MAPS (Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship) fail to adequately sample their populations. We respectfully ask that you consider supporting the Hummingbird Monitoring Network as a multi-member cooperative project for the DSCESU.

TABLE 1: The current and potential partnerships with HMN and DSCESU members.

DSCESU Member

|

Current Partnerships

|

Potential Partnerships

|

Federal agencies

|

|||

BLM

|

Big Morongo preserve is a CA monitoring site

|

Additional monitoring sites and working with TNC to address Research Question 1.

|

|

USFS

|

One AZ monitoring site and many private sites within US Forest boundaries

|

Forests are likely the habitat that hummingbirds use most. We would like you to consider additional monitoring sites and working with us on Research Question 3.

|

|

NPS

|

Funding for monitoring sites, banding materials, and educational tools. Involvement of NPS personnel in monitoring

|

Additional monitoring sites such as Big Bend and help with research questions

|

|

DOD

|

|

In AZ, the Huachuca Mtns likely support the most hummingbird species and long-term monitoring sites are needed. Ft Huachuca could provide the best site. Also, we lack monitoring sites for Costa's that prefers desert habitat where much of DOD property occurs.

|

|

USGS

|

USGS Bird Banding Laboratory supplies our bands and maintains data on each bird banded.

|

Partnering with USGS experts in population ecology would be helpful in meeting our goals.

|

|

Universities

|

|||

UC Riverside

|

Professional affiliation of Ms. Carlson and one of their reserves is a monitoring site.

|

Another reserve will be a monitoring site next year. Possible graduate student involvement.

|

|

Univ of AZ

|

Research Question 2 will be a chapter in McCaffrey's dissertation.

RNR Graduate Student, Jennie Duberstein, is designing the brochure.

|

Help with research questions 1 and 3. Help with monitoring sites, such as Mt Graham.

|

|

NM State Univ

|

|

Assistant professor Martha Desmond has expressed an interest in working with HMN. Discussions are underway.

|

|

Nongovernmental Organizations

|

|||

ASDM

|

Professional home of HMN and affiliation of Dr. Wethington

|

|

|

TNC

|

Two monitoring sites and public outreach

|

HMN would like to work with TNC and BLM with Research Question 1.

|

|

SI

|

None yet, any ideas?

|

||